Why Cheap MVPs Fail in 2026

“Cheap MVP” sounds like a smart founder move — until it becomes the reason you can’t launch, can’t iterate, or can’t trust your own product data. In 2026, speed-to-market is real, but so are the costs of fragile architecture, rushed UX, and missing analytics. This article explains where low-budget builds usually go wrong, what “lean” should actually mean, and how to spend less without paying twice.

TL;DR: Cheap MVPs fail because they optimize for the invoice, not the outcome: a working product that can be tested with real users.If you cut the wrong corners (scope clarity, UX, analytics, QA, and ownership), you don’t save money — you delay learning and burn runway.

The “cheap MVP” myth in 2026

Founders don’t actually want a cheap MVP. They want a small, fast, reliable first release.

The problem is that “cheap” usually gets interpreted as:

- “Build everything in one sprint.”

- “Skip the boring parts (QA, analytics, edge cases).”

- “Use the quickest shortcut, even if it’s hard to maintain.”

That’s how you end up with a version that looks finished but can’t survive real usage. If you’re bootstrapping, the pressure is even higher — and the mistakes are more expensive.

If you want to keep the first version lean without self-sabotage, start from feature prioritization (not hourly rates). See How to Prioritize Features When You’re Bootstrapping Your Startup.

Where cheap MVPs break first

Most low-budget MVPs fail in the same places — because these are the parts teams under-scope or under-deliver when they’re trying to “go fast.”

1) Scope becomes a moving target

Cheap builds often start with a vague spec. That sounds flexible — until every week becomes renegotiation. You lose time, the team loses clarity, and you slowly rebuild the same screens three times.

A realistic MVP scope is not “less features.” It’s one clear job-to-be-done, end-to-end.

2) UX is “good enough” until users bounce

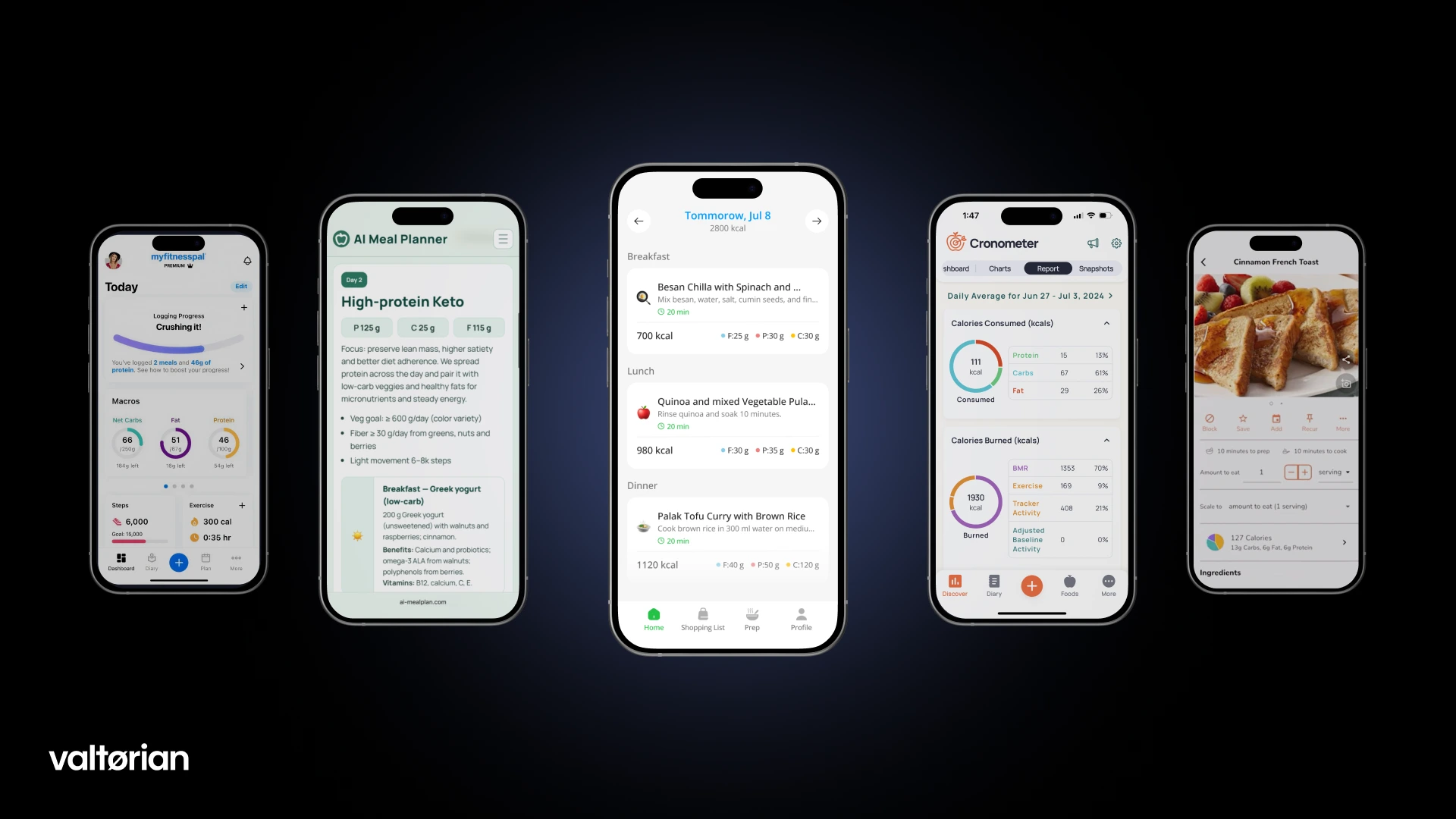

Founders underestimate how much UX affects activation. In 2026, users compare your MVP to polished consumer apps — not to other MVPs.

Bad UX doesn’t just look ugly. It creates confusion, drop-offs, support load, and fake negative signals (“people don’t want this”) when the real issue is friction.

3) Analytics are missing, so you can’t learn

This is one of the most expensive mistakes.

If you can’t answer “Where do users drop off?” or “Which feature drives repeat use?”, you can’t iterate. You’re guessing.

A cheap MVP that ships without basic product tracking is often a product you’ll need to rebuild before you can scale decisions.

If you’re not sure what early metrics should look like, read Your First Product Metrics Dashboard: What Early-Stage Investors Want to See.

4) QA is skipped, and trust collapses

Bugs are normal. Unpredictable product behavior is deadly.

When early users hit broken flows (signup, onboarding, payments, core action), you don’t get “feedback.” You get silent churn.

5) Ownership and handover are unclear

Cheap engagements often end with:

- No clean repo setup

- No deployment documentation

- No access to design sources

- No clarity on what’s actually yours

Even if the MVP “works,” you’re stuck. The next team spends weeks untangling it.

If you’re outsourcing, make sure you know what to ask before you sign. Outsource Development for Startups: Pros, Cons, and Red Flags is a good checklist-style read.

The hidden cost is not money — it’s time

The real runway killer is losing a month to:

- fixing core flows that should’ve been stable

- rebuilding features because scope was unclear

- adding analytics late (when you needed it from day one)

- replacing the team because the codebase can’t be extended

This is why cheap MVPs don’t just “fail.” They stall.

And stalling is worse than failing, because you keep paying while learning nothing.

If you want a clearer picture of how cost typically spreads across a real build, see MVP Development Cost Breakdown for Early-Stage Startups.

What “lean” should mean instead of “cheap”

A lean MVP is built to answer one question quickly:

“Will real users do the core action — and come back?”

That requires:

- a single focused workflow (not a feature list)

- clean UX for the first-time experience

- basic analytics to measure activation and retention signals

- predictable releases so you can iterate weekly

This is also why “fast” and “cheap” are not the same. Speed comes from clarity and process, not from skipping fundamentals.

If you want to see what a full path from first idea to early users looks like, read Full-Cycle MVP Development: From Discovery to First Paying Users.

A practical way to spend less without paying twice

If budget is tight, you don’t need miracles — you need constraints that protect the outcome.

Here’s a practical approach:

- Lock the MVP to one user segment and one core job.

- Build only the minimum screens needed to complete that job.

- Treat analytics and QA as “must-have,” not “nice-to-have.”

- Avoid complex roles, permissions, and admin tooling until users prove demand.

- Keep tech decisions simple unless the product truly needs complexity.

If you’re early-stage and still validating what to build, this aligns with Pre-Seed MVP Development for Unfunded Startups on a Budget.

Thinking about building an MVP on a limited budget in 2026?

At Valtorian, we help founders design and launch modern web and mobile apps — with a focus on real user behavior, clean MVP scope, and predictable delivery.

Book a call with Diana

Let’s talk about your idea, scope, and fastest path to a usable MVP.

FAQ

Is a cheap MVP always a bad idea?

No. A small MVP is often the best idea. The risk is when “cheap” means skipping scope clarity, UX, analytics, or quality — the parts that let you learn.

What’s the difference between “lean” and “cheap”?

Lean means focused: one workflow, one outcome, fast iteration, measurable learning. Cheap often means under-scoped and fragile, which slows everything down later.

What are the biggest red flags in a low-cost proposal?

Vague scope, no mention of analytics, no QA plan, unclear ownership of code/design files, and promises of “everything in v1.”

Can I fix a cheap MVP later instead of rebuilding?

Sometimes — if the foundation is clean. But if the architecture and code quality are poor, you’ll spend more patching than rebuilding.

What should I absolutely not cut to reduce cost?

Basic onboarding UX, core flow reliability (QA), and analytics for activation + retention signals.

How do I keep an agency honest about scope?

Ask for the MVP in plain language (what users can do end-to-end), and define success metrics for the first 14–30 days.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)