Choosing a Development Agency in 2026

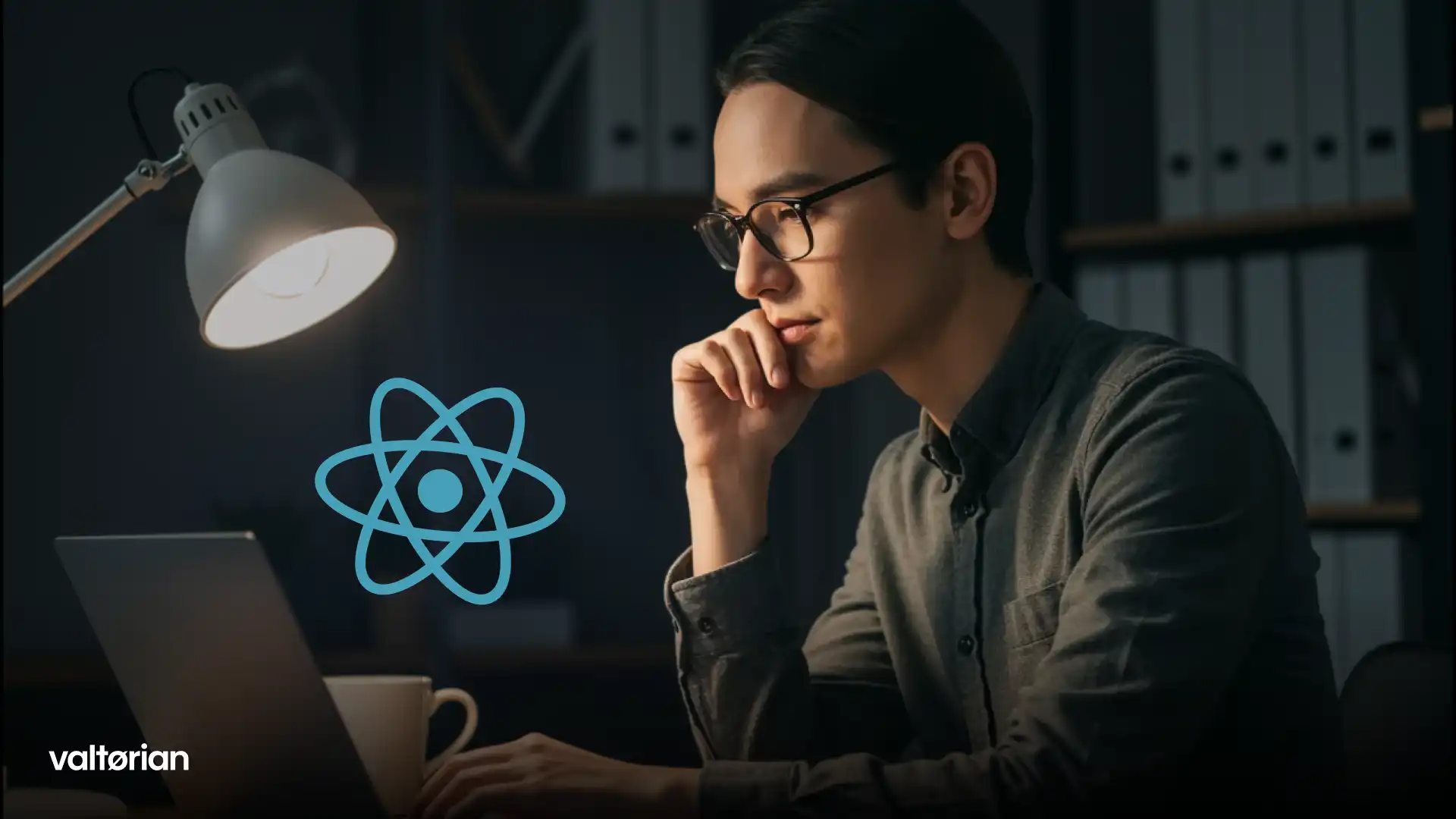

Choosing a development agency in 2026 looks easier than it actually is. AI tools can produce prototypes fast, but founders still lose months on unclear scope, mismatched teams, and “done” products that don’t work in the real world. This guide is for non-technical founders who need to pick a partner that can ship a usable MVP, keep costs predictable, and stay accountable after launch. You’ll get a practical checklist, key questions, and the warning signs to avoid.

TL;DR: In 2026, the best agencies don’t win on buzzwords — they win on clarity, senior ownership, and shipping small releases that real users can actually use.Pick the team that can define your MVP in plain language, explain trade-offs, and instrument the product so you can measure what works.

Why choosing an agency is harder (and more important) in 2026

A weird thing happened over the last couple of years: building something became cheap, but building the right thing is still expensive.

You can generate UI drafts, spin up boilerplate, and even get a clickable demo in days. But most founders aren’t paying for a demo. They’re paying for a first real version that survives:

- real users doing unpredictable things

- real devices, browsers, and edge cases

- real onboarding friction

- real data handling and integrations

- real iteration after launch

So the agency decision in 2026 is less about “can they build?” and more about “can they ship responsibly, fast, and stay accountable when the plan changes every week?”

If you’re still deciding whether an agency is even the right model for you, start with Startup App Development Company vs Freelancers vs In-House Team.

Step 1: Define what you actually need (before you speak to agencies)

Most bad agency projects start with a perfectly reasonable founder sentence:

“We need an MVP.”

The problem is that “MVP” means ten different things depending on who you ask.

Before you evaluate anyone, answer these in plain language (one sentence each):

Who is the user, exactly?

A title is not enough. “Recruiter” is not enough. Describe a real person and context.

What is the job-to-be-done?

What are they trying to accomplish in one session?

What is the first measurable outcome?

Activation is usually a better early goal than revenue. A simple example: “User completes onboarding and reaches the first successful result.”

What must be true for you to call V1 a success?

Not a big vision. One tight success condition.

What’s the deadline pressure?

Are you racing runway? Investor timeline? Market window?

You don’t need a 40-page PRD. But if you can’t answer the basics, agencies will fill in the blanks — and you’ll pay for their assumptions.

To get a clean baseline for what an MVP should include (and what it shouldn’t), read MVP Development Services for Startups: What’s Actually Included.

Step 2: Understand what you’re buying (it’s not “development”)

Founders often compare agencies like they’re buying a commodity: hourly rates, headcount, shiny portfolios.

In reality, you’re buying four things:

1) Product decisions under uncertainty

Any team can build tickets. The question is who helps you decide what not to build.

2) Risk reduction

Good agencies surface risk early (scope, integrations, performance, compliance, app store constraints) instead of discovering it late.

3) Speed with control

Fast iteration is only valuable if it doesn’t create future chaos.

4) Accountability after launch

A surprising number of teams treat launch as “handoff.” In 2026, launch is when the work becomes real.

If you want a practical view on what “full-cycle” should mean in a startup context, use Full-Cycle MVP Development: From Discovery to First Paying Users.

Step 3: What a strong agency looks like in 2026

Here’s the simplest signal: a strong agency can explain your MVP back to you in plain language, including trade-offs.

Below are the traits that matter most in 2026.

They force clarity on scope (without being annoying)

A good team will push back on vague scope, not because they’re difficult — but because scope creep is the #1 silent killer of runway.

A useful pattern is a “smallest usable version” definition:

- what must exist for a user to complete the core job

- what can wait until real usage proves it matters

- what is explicitly out of scope for V1

This is also why cost estimates vary so much. If you want to understand how agencies should break down MVP cost (and what can inflate it), see MVP Development Cost Breakdown for Early-Stage Startups.

They have senior ownership, not just delivery

A polished pitch with juniors doing most of the work is the most common mismatch.

You want to know:

- Who is responsible for architecture decisions?

- Who is responsible for product decisions when trade-offs appear?

- Who talks to you weekly?

If the answers are “account manager,” “delivery manager,” or “someone you’ll meet after contract,” be careful.

They treat analytics as part of the build (not an optional add-on)

In 2026, “we shipped” is not a success metric.

A strong agency will help you define:

- what events matter in the first 7–30 days

- what your activation metric is

- what dashboard you’ll use to track behavior

If you need a founder-friendly view of what investors actually want to see early, read Your First Product Metrics Dashboard: What Early-Stage Investors Want to See.

They know how to use AI without turning your product into a science project

AI can speed up delivery and improve workflows — but it can also blow up scope fast.

A good agency will separate:

- deterministic logic (rules, flows, validation)

- probabilistic logic (AI outputs)

- fallbacks when AI is wrong

This matters even if your product is not “AI-first.” The wrong team will propose AI because it sounds modern. The right team proposes it only where it removes real risk or friction.

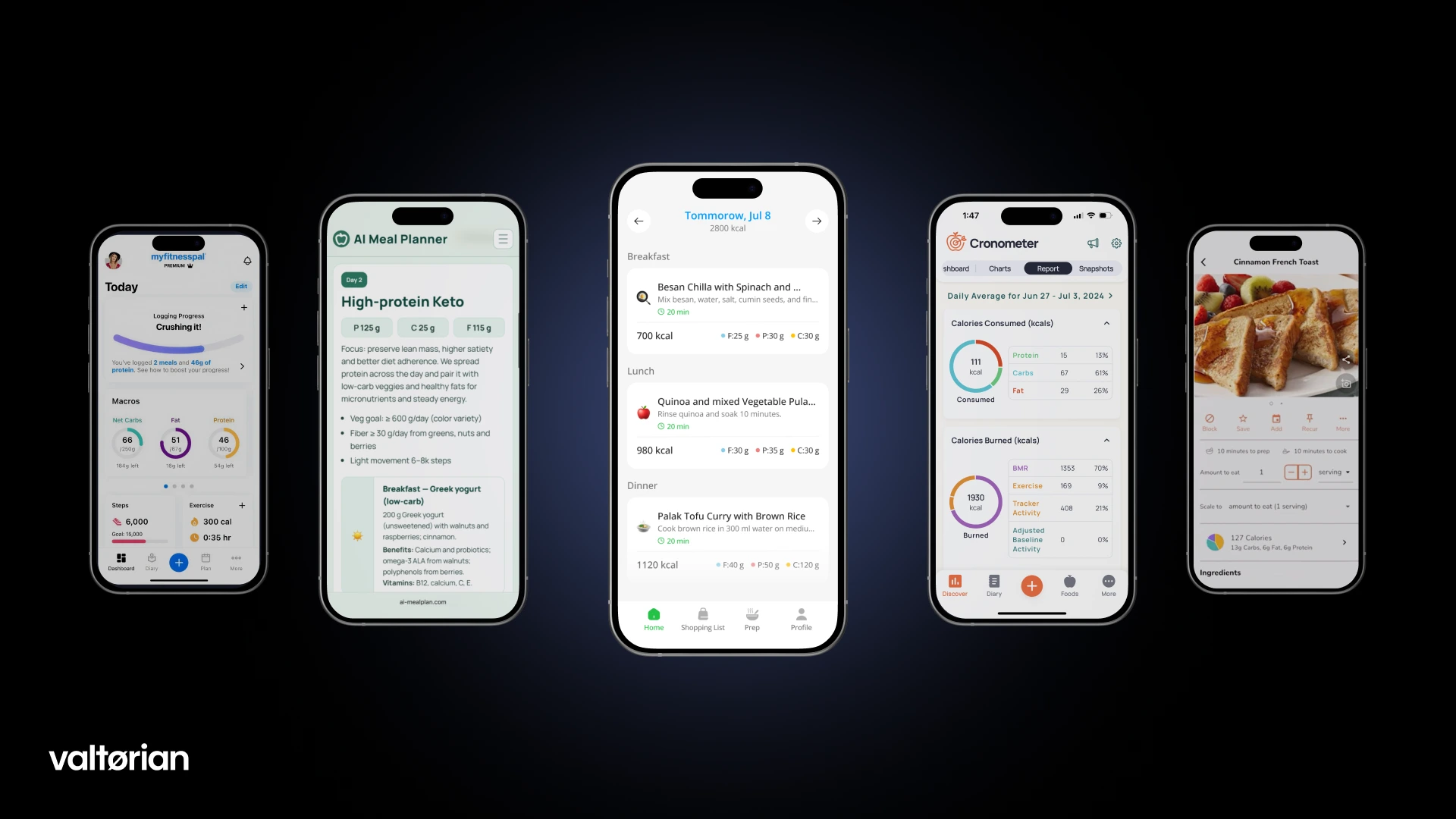

For the deeper difference between an “AI agency” and a product team that uses AI correctly, see AI Development Agency vs Classic Development: What’s the Difference for Founders?.

Step 4: The questions that reveal everything (use these on the first call)

You don’t need tricky interview questions. You need questions that force the agency to show how they think.

1) “What would you ship in the first 4–8 weeks — and what would you cut?”

Strong answer:

- a short scope description (not a roadmap)

- a clear V1 user journey

- an explicit list of “later” items

Weak answer:

- a long feature list

- “it depends” with no attempt to propose a baseline

2) “What do you do when requirements change mid-build?”

Strong answer:

- change control process

- trade-offs and re-prioritization

- communication cadence

Weak answer:

- “we’ll handle it” (with no process)

3) “How do you keep quality high without slowing down?”

Strong answer:

- QA strategy (manual + automated where it matters)

- staging environments

- release process

Weak answer:

- “we test everything” (with no specifics)

4) “How do you prevent building features nobody uses?”

Strong answer:

- small releases

- early user feedback loops

- analytics and activation tracking

Weak answer:

- “we follow the spec”

If you haven’t validated the problem yet, a good team will suggest light validation before a full build. A practical starting point is Validate a Startup Idea Before Development: 5 Experiments That Work.

Step 5: The red flags that cost founders months

These aren’t “bad people” signals — they’re “you’re about to waste runway” signals.

Red flag 1: They quote fast without clarifying anything

Speedy estimates feel good, but they usually mean the scope is imaginary.

Red flag 2: They sell the biggest version of your idea

If the team is incentivized to grow scope, you’ll get a big build, late launch, and weak learning.

Red flag 3: They avoid trade-offs

If everything is “yes,” you’re not getting product leadership.

Red flag 4: They can’t explain ownership

If you don’t know who owns design, architecture, QA, releases, and metrics — you’ll feel it later.

Red flag 5: They vanish after launch

If the agency treats launch as the finish line, you’ll be alone exactly when you need iteration the most.

If you want a deeper list of what to watch for when outsourcing, read Outsource Development for Startups: Pros, Cons, and Red Flags.

A practical way to structure the engagement in 2026

You don’t need a complicated contract structure. You need one that matches reality:

Option A: Short discovery - build

Best when:

- scope is fuzzy

- multiple user types exist

- you’re unsure what the core workflow really is

Option B: Build-first with strict scope guardrails

Best when:

- you’ve validated the problem

- you can describe the first user journey clearly

- you’re optimizing for speed to first users

Either way, insist on:

- a clear MVP definition (in plain language)

- what is out of scope

- a release cadence (weekly or bi-weekly)

- a simple change process

This keeps the relationship honest and predictable — especially for non-technical founders.

Thinking about building a web or mobile app in 2026?

At Valtorian, we help founders define a realistic MVP, ship fast, and track real user behavior — with a small founder-led team, not a chain of account managers.

Book a call with Diana

Let’s talk about your idea, scope, and fastest path to a usable MVP.

FAQ

How do I know if an agency is “too big” for my startup?

If you’re early-stage, too many roles and handoffs often slow decisions. Ask who you’ll work with weekly and who owns trade-offs.

Should I start with discovery, or can I go straight to development?

If the user workflow is still fuzzy, a short discovery saves money. If you have clear validation and a tight first journey, you can build-first with strict scope guardrails.

What’s the single most important thing to align on before signing?

A plain-language MVP scope: what V1 includes, what it excludes, and what “success” means in the first 30 days.

How do I compare agencies beyond portfolio screenshots?

Ask for a proposed MVP scope, release cadence, and how they handle changes. The best teams make trade-offs visible.

What should be included in an MVP contract by default?

Clarity on scope, ownership of deliverables, a predictable communication cadence, and a simple change process.

How can I avoid overbuilding in 2026?

Ship the smallest usable version, instrument activation, and iterate based on behavior — not opinions.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)