Startup Validation Mistakes in 2026

Validation in 2026 is confusing because building got faster, but proving demand did not. Founders can ship a prototype in days and still spend months wondering why nobody sticks around. This article breaks down the most common validation mistakes we see in early-stage startups — especially with non-technical founders — and shows what to do instead. You’ll learn how to separate interest from intent, run lightweight experiments, and define clear “go / pause / stop” criteria before you commit real budget to an MVP.

TL;DR: Most startup validation fails in 2026 because founders test opinions instead of behavior.If you validate the workflow, the buyer, and the willingness to pay (with clear stop rules), your MVP scope becomes obvious and cheaper.

Why validation feels harder in 2026 (even though building is easier)

In 2026, almost any founder can generate a landing page, a clickable prototype, or even a half-working app quickly. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that speed creates a new trap: you can build something so fast that you skip the hard part — proving that real people will change their behavior for it.

Validation is not “Does this sound like a good idea?” Validation is “Will someone do the uncomfortable thing required to adopt it?” (Pay, switch tools, share data, invite a teammate, complete setup, come back next week.)

If you validate those behaviors early, you don’t need a huge MVP. You need a small product that makes the first behavior feel easy.

8 validation mistakes founders still make in 2026 (and how to fix them)

1) Confusing compliments with demand

A classic: people say “Nice idea” and you hear “I will use this.”

Fix: Define one concrete action that equals intent (join a waitlist with a specific use case, pre-order, book a demo, submit data, agree to a pilot). If you can’t get the action, you don’t have demand — you have politeness.

If you want a clear set of experiments that test behavior, see Validate a Startup Idea Before Development: 5 Experiments That Work.

2) Interviewing the wrong people (because they’re easy to reach)

Friends, founders in communities, and “people who love startups” are not your market. They’re usually too supportive and too generic.

Fix: Recruit interviews from the environment where the pain actually happens (the job role, the workflow, the decision context). If you’re B2B, talk to the buyer and the daily user separately. If you’re B2C, talk to people who tried to solve it recently — not “someday.”

3) Asking hypothetical questions

“Would you use this?” produces fantasy answers.

Fix: Ask for the last time they experienced the problem and what they did instead. Then ask what happened, what it cost them, and what they disliked about the workaround.

A simple pattern:

- “When did this happen last?”

- “What did you do?”

- “What was annoying / risky / expensive about that?”

- “What would you pay to remove that pain this month?”

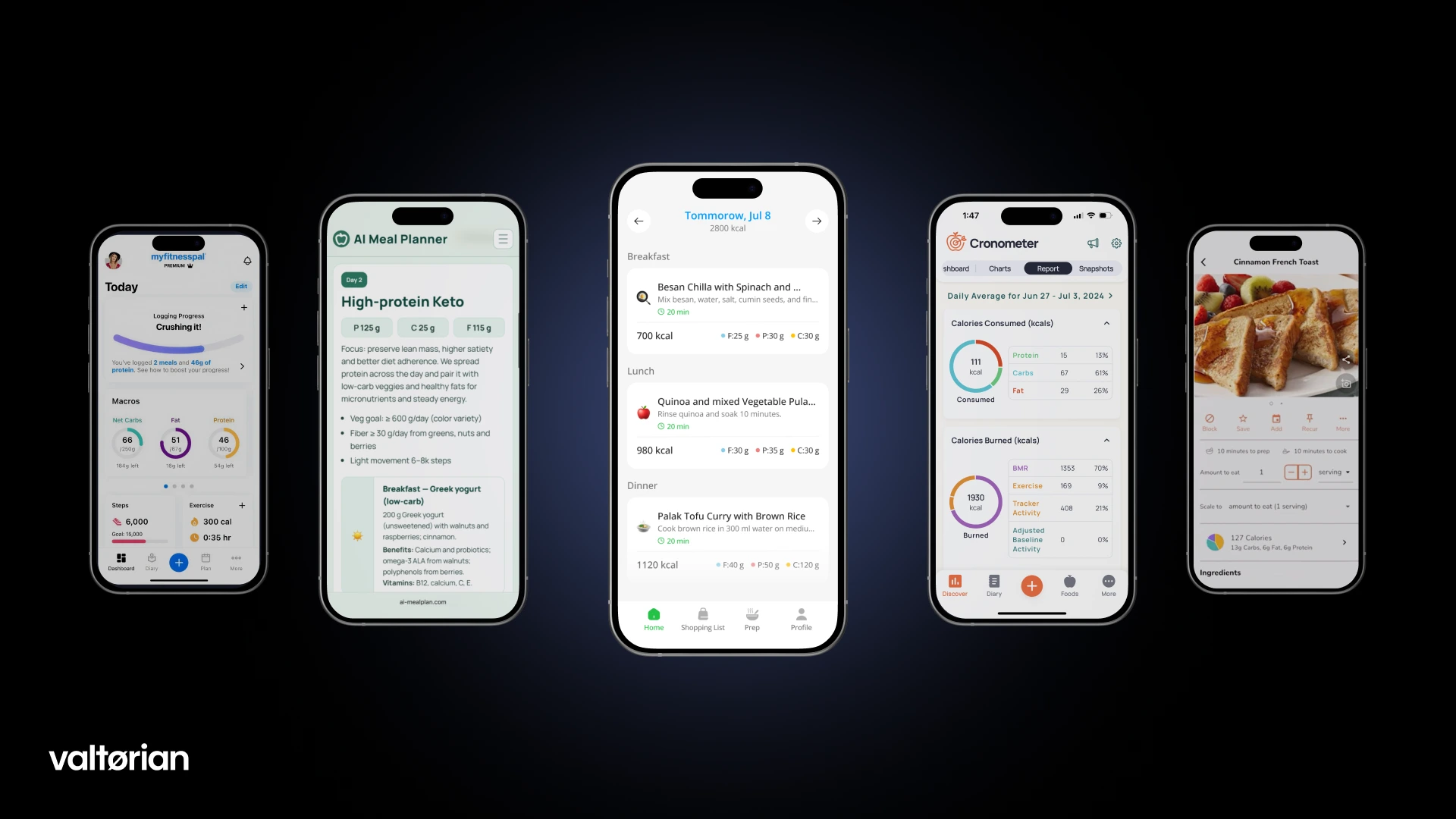

4) Validating a feature instead of a workflow

Founders validate a feature idea (“AI planner”, “dashboard”, “chat”) when users actually buy a workflow outcome (“save 2 hours weekly”, “reduce errors”, “close faster”).

Fix: Draw the workflow in 6–10 steps. Mark where time, money, risk, or frustration spikes. Validate that spike first.

If you struggle to translate messy needs into a small first release, read Choosing an MVP Development Company as a Non-Technical Founder.

5) Skipping willingness-to-pay (or doing it too late)

Many teams validate “interest” and only talk about pricing after they build. That’s how you end up with a product that people like but won’t buy.

Fix: Test pricing as early as you test the problem.

- For B2B: test a pilot price, a monthly price, and what internal budget it would come from.

- For B2C: test a specific subscription number and the trigger that makes it “worth it.”

Not everyone will answer honestly, but the shape of the answer tells you if the pain is real.

6) No stop rules (so validation never ends)

Some founders “validate” for months because they don’t know what result would mean “go.”

Fix: Define success and failure before you start.Example:

- Go if: 25% of qualified users take the intent action within 14 days.

- Pause if: interest is high but intent action is low — the workflow may be wrong.

- Stop if: the pain isn’t frequent enough or the buyer isn’t clear.

This is the same mindset we apply in How to Prioritize Features When You’re Bootstrapping Your Startup — you don’t earn the right to build everything.

7) Measuring vanity metrics instead of the first real behavior

Traffic, likes, and waitlist size can be useful, but they’re not the product.

Fix: Pick one “first value” behavior and instrument it early.Examples:

- B2B: “invited teammate” or “created first project”

- B2C: “completed setup” and “returned within 7 days”

If you need a practical way to connect behavior to investor-ready clarity, see Your First Product Metrics Dashboard: What Early-Stage Investors Want to See.

8) Overbuilding the MVP because the idea feels fragile

When founders are unsure, they add more features to “increase the chance of success.” In practice, it increases cost and makes learning slower.

Fix: Build the smallest version that can deliver the first value outcome.Your MVP is not a mini “full product.” It’s a learning machine.

If you’re unsure what “smallest useful” actually looks like, start with What a Good MVP Looks Like in 2026.

A practical validation kit for non-technical founders

If you want a simple checklist you can run without a tech team, here’s what to prepare before spending meaningful budget:

- One target user (job role + context). Not “everyone with this problem.”

- One workflow promise (the outcome that matters in plain language).

- One intent action that proves commitment.

- One pricing guess (even if it changes later).

- One stop rule (what result means “don’t build this now”).

Once you have these, MVP scope becomes a structured decision — not a debate.

When to stop validating and start building

A good signal to build is when:

- You can describe the user and workflow without hand-waving.

- You see repeated pain patterns (not one-off curiosity).

- People take the intent action at a rate that matches your business model.

- The first version can be defined in plain language.

At that point, your next risk is speed-to-market and execution, not idea uncertainty. A simple launch path is covered in How to Launch an App in Weeks: Fast MVP and First Version Launch Framework.

Thinking about validating and building your MVP in 2026?

At Valtorian, we help founders turn early ideas into modern web and mobile apps — with lightweight validation only where it removes real risk.

Book a call with Diana

Let’s talk about your user, your scope, and the fastest path to a usable first version.

FAQ

How many user interviews do I need to validate an idea?

Enough to hear the same pain pattern repeatedly. For many early-stage ideas, 10–15 high-quality interviews can be more useful than 100 random opinions.

Can I validate without building anything?

Yes. Landing pages, pre-orders, concierge pilots, and paid discovery calls can validate intent before you write a line of code.

What’s the biggest validation red flag?

When people like the idea but won’t commit to a concrete next step (pay, pilot, share data, schedule time, or switch workflows).

Should I validate pricing before the MVP exists?

Yes. You don’t need perfect pricing, but you do need a believable range that matches the pain and the buyer’s budget.

What if my audience is small but high-value?

That can still work. The key is whether you can reach them repeatedly and whether the problem is frequent enough to justify ongoing payment.

How do I avoid building the wrong MVP scope?

Anchor scope to one workflow outcome and one measurable first-user behavior. If a feature doesn’t support that, it belongs in “later.”

When is it okay to skip validation?

When you already have clear traction signals (paid pilots, committed users, or an existing workflow you’re replacing) and the remaining risk is execution.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)